A mention of the year 1930 might remind most Indians of the Civil Disobedience Movement and the Dandi March. But down south, in the princely state of Mysore, in the deep, dark and dangerous mines of Kolar Gold Fields (KGF), the flames of a very peculiar proletarian struggle were being kindled around the same time.

It was a serendipitous discovery for historian Janaki Nair when she came across a report about the general strike of mine workers at KGF in The Hindu newspaper dated April 6, 1930, the same day Gandhiji broke the salt law. Nair, who has extensively researched and written about the general strike of 1930 at KGF, recently spoke at the Bangalore International Centre (BIC) as part of a series of lectures on subaltern struggles in the princely state of Mysore.

The 21-day long strike by an 18,000-strong workforce against a new system of fingerprint registration introduced by John Taylor & Sons has a special place in the list of labour movements given how the workers mobilised under no obvious leadership and succeeded at bringing the company to meet their demands.

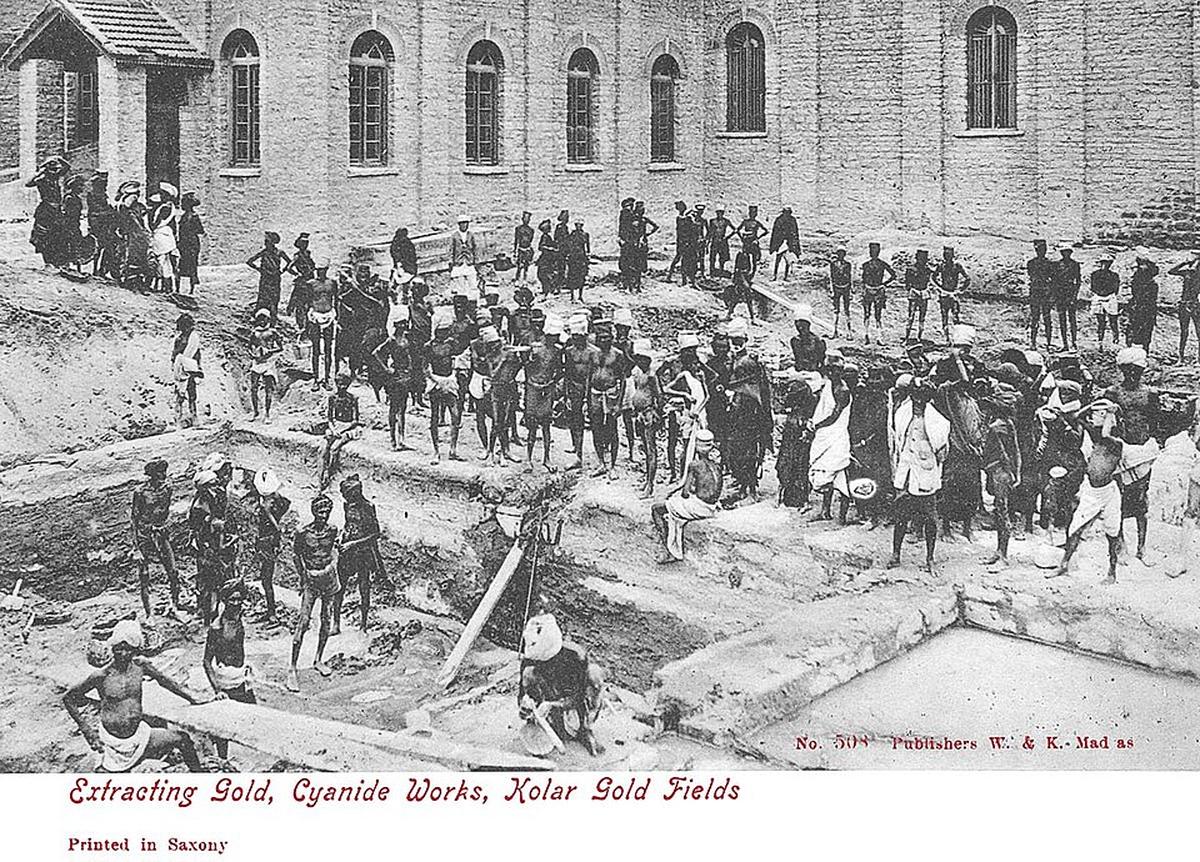

Extracting Gold, Cyanide Works, Kolar Gold Fields.

| Photo Credit:

WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

The anonymous notice

The first news report on the strike appeared in The Hindu on April 4, 1930, under the headline “Kolar Gold Field – The Oorgaum Mine Strike.”

The events, however, started unfurling on April 1, 1930, says Nair, when an anonymous notice was found attached to a rock in KGF urging the mining workers to stop providing their fingerprints.

The company’s explanation for introducing the new registration was that it needed to register all workers and be able to identify them to fulfill obligations under the Workman’s Compensation Act introduced in Mysore in the previous year in 1929.

“The anonymous notices which sprang up in different parts of this 75 square mile area were asking workers to simply stop work from April 8 until the new registration system was withdrawn,” Nair notes.

What was the workers’ beef against the new registration system?

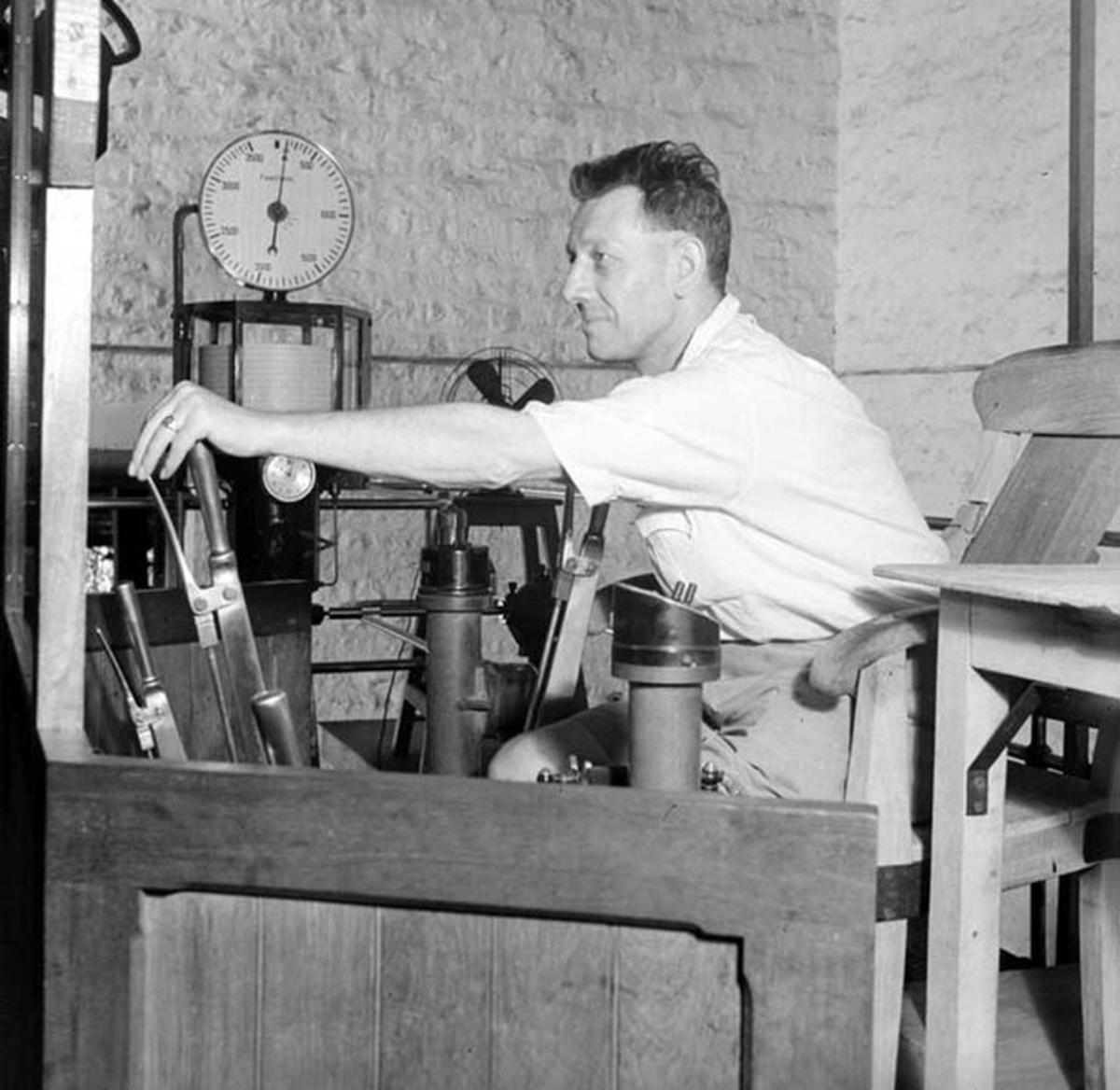

The winding engine operator at his platform, He controls from here the movements of the cages in their Journey up and down the mine.

| Photo Credit:

WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

Strict regulations

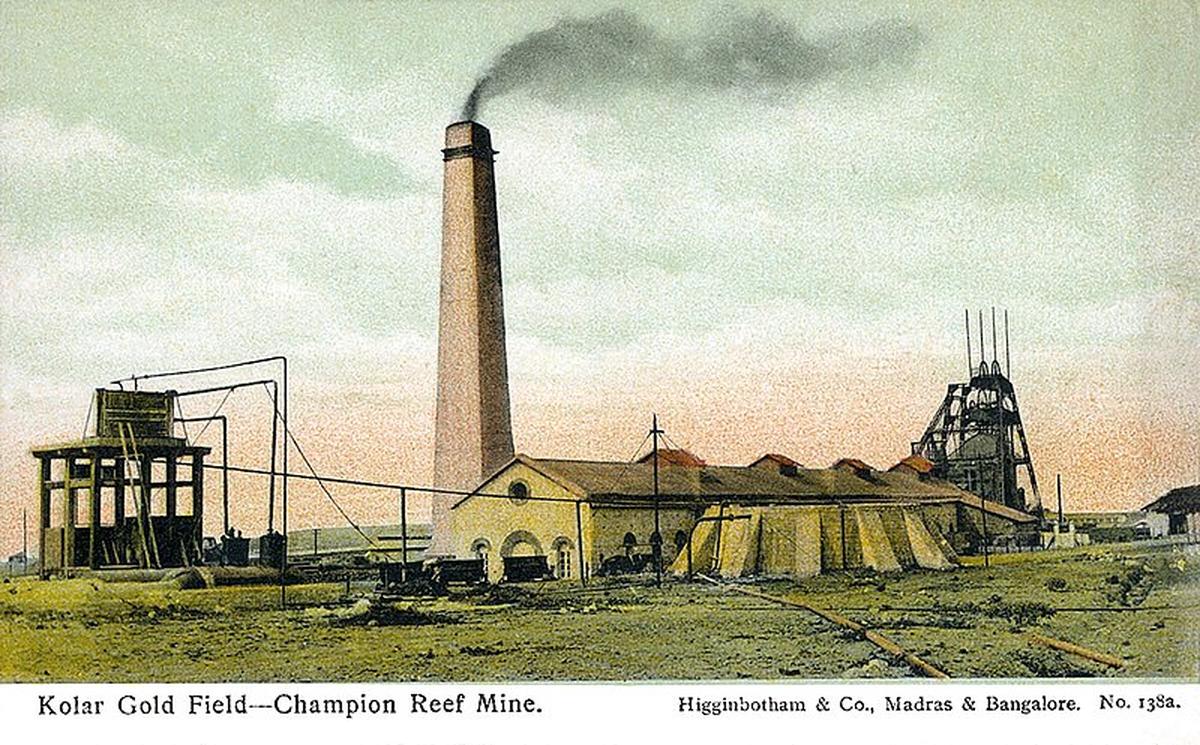

The discovery of the champion lode or the richest gold vein in KGF was in the late 1880s. The worker numbers rose from around 6,000 to a whopping 36,000 by 1907 and dropped to about 18,000 by 1930. The four mines of KGF constituted the largest enterprise in Mysore state.

Given the precious nature of the product and the large size of the workforce, John Taylor & Sons imposed very strict rules to govern the region. Nair refers to it as the “Company State.”

“In some ways, the company was the state in this particular region. The state government did not have much to say or do in terms of regulations that were operating in the KGF,” she explains.

Among the strictest rules put in place was the Mysore Mines Regulations, 1906, which, in Nair’s words, developed a new taxonomy of crime itself.

“All those who were in possession of any form of unwrought gold were punished. There had to be very strict system of licenses for traders and merchants in the area. There was a strict ban on a certain category of people called the ‘undesirables.’”

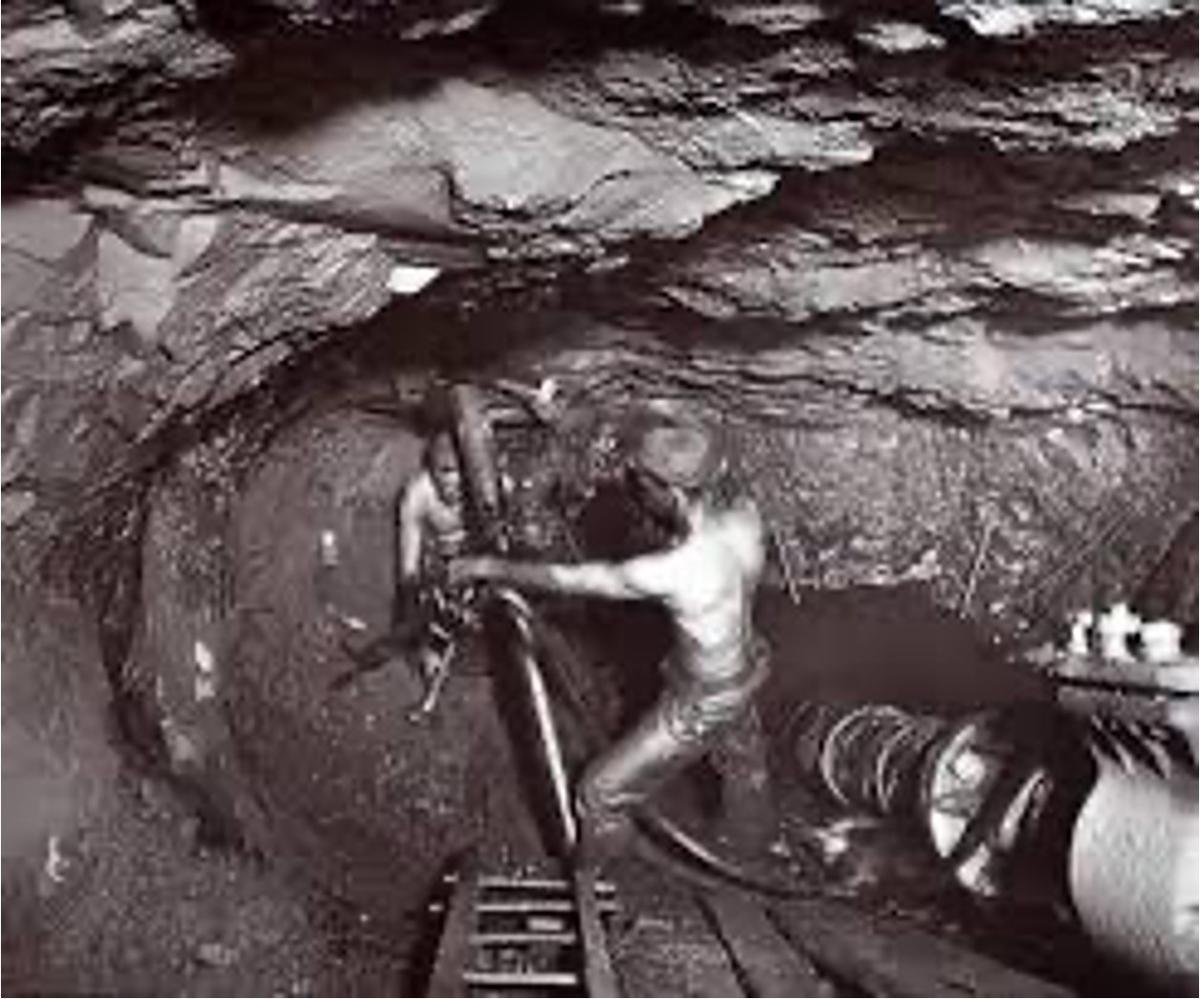

The working conditions were precarious and dangerous, to say the least. KGF mines were among the deepest in the world with Oorgaum mine going down to 8,000 feet or about 2.5 km.

| Photo Credit:

SPECIAL ARRANGEMENTS

Abysmal work conditions

“In addition to the Mysore Mines Regulation of 1906, in 1916 Mysore Criminal Tribes Act came into being and was exclusively operating only in KGF,” Nair points out. It identified five sets of tribes – Gantichors, Kepmaris, Woddars, Korachars and Koravas – as criminal tribes and placed them under forms of surveillance which were extremely pervasive and obnoxious, she adds.

While the company could not operate without the help of these tribes whose skills were very essential to mining, they used the Acts to keep a close eye on them. Nair explains this with the example of Woddars who were traditionally well-diggers and hence crucial for mining operations.

“The Woddars, for instance, under the Criminal Tribes Act, were expected to be physically examined. Their orifices were examined from mouth to anus to vagina and they had to simply subject themselves to this kind of examination if they wanted to continue to labour in this region.”

The working conditions were precarious and dangerous, to say the least. KGF mines were among the deepest in the world with Oorgaum mine going down to 8,000 feet or about 2.5 km. The deep hot mines witnessed a very high number of accidents. Often, the workers themselves were blamed for it by the company.

“The heat question was something that the company was unwilling to deal with. Air conditioning was finally introduced in KGF only in the 1930s. The excuses that were given to not provide certain kinds of facilities was that natives are used to working in very high temperatures and therefore they can tolerate higher temperatures. The kinds of facilities that were offered to these workers were kept to the very bare minimum,” Nair says.

There was also the distinction between the company and the contract coolies. While a portion of workers worked directly for the company, around 55% of them were provided by contractors making the lives and livelihoods of the latter further precarious.

But what Nair finds interesting is how, even in such a repressive system, the workers found a new sense of meaning and self-worth. Most workers were migrants from the dry districts of Chengalpattu, Salem and North Arcot in Madras Presidency, where bonded labour was the norm. Money wages, therefore, became a form of liberation for the migrant workers of KGF. They earned a respectable wage between Rs 23 and 25 rupees a month which went up to Rs 50 for a mesthiri.

A new sense of identity and dignity was taking shape among the workers and the fingerprint registration was a question mark posed on it.

Workers in Kolar Gold Mine.

| Photo Credit:

WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

The tipping point

While the workers earned decent wages for the times, around 80% of them were heavily indebted to the Marwari moneylenders in the region, points out Nair. The moneylenders also managed to persuade the company to allow them to attach the salaries of the gravely indebted workers.

“There was a complete complicity between the company and the moneylender… Sometimes the worker was indebted up to five or six times his monthly salary,” Nair notes.

It was to such tense and strenuous circumstances that the fingerprint mandate was introduced.

“Finger printing was also a way that was introduced to identify the criminal tribes. So, finger printing was associated very strongly with ideas of criminality which in Mysore was applicable only to the KGF areas,” says Nair.

For the worker who was already doing a very dangerous labour, the notion of being considered a criminal on top of it or his identity verging on criminality must have been the tipping point.

“There was full understanding of the dangers of work in this area. There was also full understanding of the kinds of restraints and surveillance measures that were being imposed on workers in this area,” Nair says.

Having a central registry of workers also meant contract workers who used to work in multiple mines under different contractors would be prevented from doing so.

“They felt there was no reason to be enslaved onto the mines. They had a very clear picture of what work meant and what it did not mean. And it did not mean committing yourself to this kind of bondage,” Nair adds.

By April 12, more demands such as grant of hospital and sick pay, service money to contract labourers, full strike pay, contract labour to be on same footing as company labour for attendance bonus, recognition of labour representatives and abolition of employment office in any form made it to the list.

With the workers standing their ground and many of them beginning to leave for their native places, the company was not left with a choice. The nearly 7,000 fingerprints which it had collected were destroyed in the presence of a Mysore government bureaucrat and around 2,000 workers.

“The workers came back to work about 21 days later, but not before the state government had taken grave notice of the difficulties that had set in KGF and had sent Diwan Mirza Ismail to look into it,” Nair notes.

By 1904 the Kolar fields produced nearly all the gold in India, valued at over 20 million pounds sterling annually.

| Photo Credit:

WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

A unique fight

One of the most prominent features of the strike was the lack of any obvious leadership and the communication through anonymous notes. The strike also witnessed a unique kind of solidarity between the company workers and contract workers which wasn’t witnessed prior to it.

“They were clear that the registry was a threat to all workers, not just to company or contract workers,” Nair notes.

She also observes that KGF was a location where new forms of self-definition were emerging as a consequence of political influences and economic liberty brought in by money wage.

“There was no question of a return to certain forms of extra economic coercion, which they felt was implied in the collection of the fingerprints.”

According to Nair, it was an extraordinary occasion because there aren’t many examples of workers striking for something other than conditions of work, wages and so on.

“This strike was not about wages. Strictly speaking it wasn’t even about working conditions. It was about dignity and self-worth which the workers were not willing to sacrifice in order to continue to work in these mines,” says Nair who also makes a direct parallel with the current times.

“We are constantly asked by the State to identify ourselves, provide what they call ‘know your customer’ documents over and over again. At the same time the state is becoming more and more inscrutable, and less transparent. So, this historical hostility to forms of identification are actually quite important and interesting to us as forms of resistance against this insistence on identification.”

(This is the second of a two-part series based on Janaki Nair’s masterclass on social history and subaltern figures from the Princely State of Mysore. Her lectures can be accessed at BIC’s YouTube channel.)

Published – March 20, 2025 09:00 am IST

Discover more from

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Be the first to comment